As you well know, BioMARató is a friendly competition that aims to census marine biodiversity based on photographs taken by citizens. Just the fact of contributing to science with our photographs is already very satisfying for many people like us, isn’t it? We like to go to the water to enjoy ourselves and know that at the same time we can contribute to knowing more about what we are seeing and helping the world of biodiversity research.

This science is used in a wide variety of research fields, with most publications focused on biology and conservation. The data obtained thanks to the contribution of all the participants are used by researchers from the Institute of Marine Sciences (ICM-CSIC) and elsewhere in the world, to learn more about our planet. As you can imagine, the scientific community would not have enough financial or personal resources to be able to obtain so much data, so your contribution is essential. The observations obtained in citizen science projects such as BioMARató also contribute to the UNESCO Sustainable Development Goals, a series of universal and integrative objectives that address different themes, including the fight against climate change and the protection of the planet. These goals must be the script for the United Nations when implementing its action agenda between now and 2030. That is why all the information that can be provided about our marine and coastal biodiversity is important, in order to have enough data to propose actions in favor of its protection.

But once you have recorded your observations, you wonder: how is this data processed and interpreted? When you record an observation in MINKA —whether of a species of flora or fauna— this information goes through different phases. First, the quality of the data is ensured. This means that experts review the species identification to validate that it is correct.

Patterns and changes in biodiversity

Once validated, the data is classified based on its geographical location and date. This data is compared with other records to detect patterns and changes in biodiversity. For example, it can reveal whether a species is expanding or shrinking in certain areas or whether there have been alterations due to factors such as climate change or pollution. An example is the invasive alga Caulerpa cylindracea, which has gradually been detected in new areas.

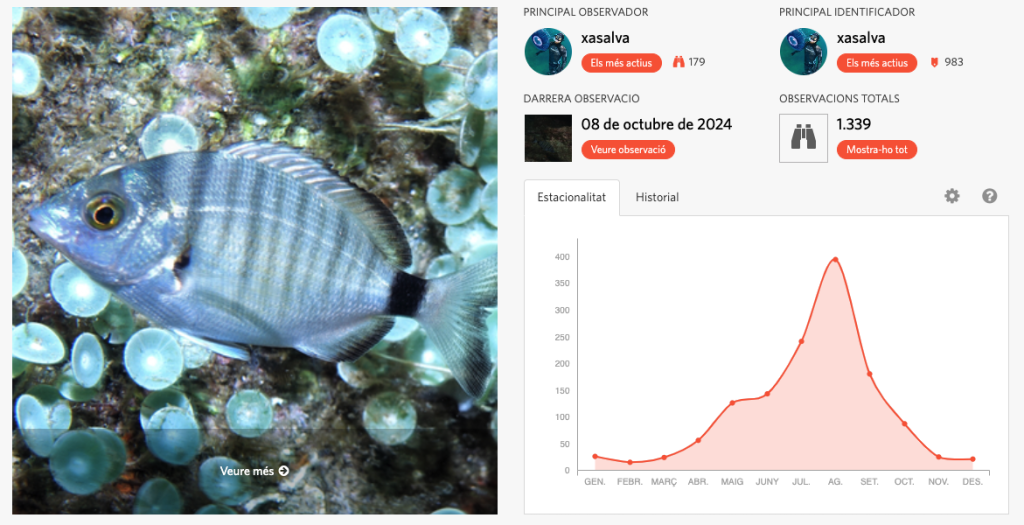

Foto: xasalva, MINKA

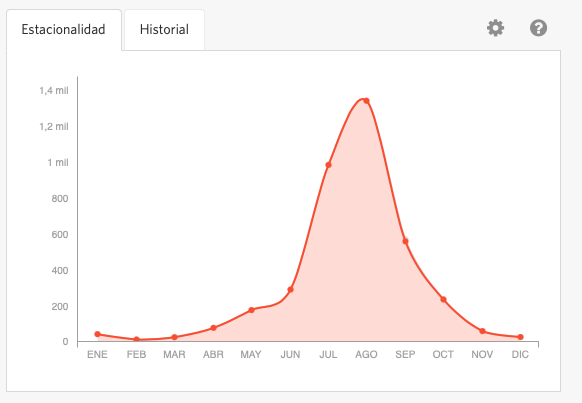

The maps also give us a lot of information about the distribution of species. For example, if we look at the peacock wrasse Thalassoma pavo, which is one of the most observed species during this Biomarathon 2024. If we look at the observations throughout the year, do you think this curve in the graph is due to the fact that the peacock wrasse only shows its head in the summer, and hides in the winter? Or do you think it is due to the fact that you, as volunteers, only take photographs in the summer because you are cold in the winter? We’ll let you guess.

Foto: josepdegea, MINKA)

Impact of climate change

Long-lasting heat waves are one of the most worrying effects of climate change, and are having a devastating impact on coral colonies in the Mediterranean, especially species such as Eunicella singularis and Paramuricea clavata. These species play a vital role in marine biodiversity, as they create three-dimensional habitats where many other marine species find shelter and food.

Using MINKA, users can document the health of Eunicella singularis and Paramuricea clavata colonies before, during, and after heat waves. This allows researchers to observe how colonies change over time and what factors influence their resilience or vulnerability. The data obtained on the health of these corals can be compared with environmental conditions, such as water temperature, to better understand the relationship between heat stress and coral mortality.

Foto: carlos88, MINKA

The data collected through MINKA has enormous value for long-term research. Scientists can use it to detect trends, study species behavior, and create predictive models of how biodiversity will evolve in the future. So your contributions as a citizen not only have an immediate impact, but also contribute to large-scale projects that can influence decision-making about the conservation of species and habitats.

Being part of the MINKA community is much more than taking photos or recording observations. It’s becoming a key piece for science, helping to transform data into information that can guide environmental policies and concrete actions. If you want to contribute your bit to environmental protection and become a scientist for a day, participating in citizen science projects like MINKA is the perfect way to do it!

Author of the article: Judith Camps Castella (Plankton, Outreach and Marine Services).